I am very humbled to announce that my original article on this topic has now had to be removed as it has been published by The Lawyer magazine.

Please follow this linkhttp://ml2b.thelawyer.com/3027417.article?mobilesite=enabled

Thank you so much to each one of you 1800 readers I could not have done this without you.

Kelly Thornton

A legal blog looking at recent cases, current legal affairs and making a career in law.

Search

Wednesday, 22 October 2014

Tuesday, 7 October 2014

Transatlantic Trade deal: A global union or a constitutional nightmare?

The Transatlantic trade deal: what is it?

The purpose of the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) is a deal which will enable the US and EU to remove their regulatory differences. Prima facie, this seems like a great idea and a good way to create a more global and free market however with the shock statement from Lord Livingstone yesterday saying that this deal will include the NHS it seems the deal will do more damage than good.

For more information on what the TTIP is please see: http://www.independent.co.uk/voices/comment/what-is-ttip-and-six-reasons-why-the-answer-should-scare-you-9779688.html

The issue

The problem with the TTIP is it will provide businesses with the power to sue governments whom defending their citizens. Many legal theorists and lawyers take issue with the TTIP because It would allow a secretive panel of corporate lawyers to overrule the will of parliament and destroy our legal protections. This goes against the key principle of the UK's constitution: Parliamentary Sovereignty.

The mechanism through all this will happen is known as investor-state dispute settlement. The shocking news is that this settlement is already being used in many parts of the world to destroy regulations protecting people and the planet. Investor-state dispute rules found in in trade treaties allow companies to sue the countries that signed the treaties. Worryingly the rules are enforced by panels which are not safe-guarded, the hearings are secret and the judges are corporate lawyers, many of whom work for companies of the kind whose cases they hear. This is all gobsmackingly unconstitutional and the defenders of fair trials and human rights are up in arms about it. Secret hearings limit the public's right to see current cases published and this risks clouding the Rule of Law and creating a less transparent and unjust legal system here in the UK. The idea that some of the judges may be biased means that the defendants will never be guaranteed a fair trial, a human right under the HRA 1998 s 6. Worst still is the fact that this entire system is not subject to appeal as citizens and communities affected by their decisions have no locus standi.

For more information surrounding the debate about the Investor- state dispute settlement please see this great opinion piece in the Washington Post http://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/debating-the-investor-state-dispute-settlement/2014/10/05/2c2477ec-4b15-11e4-a4bf-794ab74e90f0_story.html

The NHS

The big worry surrounding the TTIP is that it could lead to the NHS being bought by a big commercial player and there is nothing that we can do to prevent this. It will give big business vast new powers over public services which could see our human rights breached and environmental protection rules disregarded.

For a more detailed analysis of the threat to the NHS please see: http://www.theguardian.com/business/2014/sep/07/trade-unions-trade-deal-threat-to-nhs

Conclusion

The conservatives have been made aware of the opposition to the TTIP and suggest that it will benefit the UK by £10bn but statistics also show that 1m jobs will be lost in the EU. The conservatives are trying to kill off the opposition by insisting that those opposing the TTIP are simply anti-american and that this is too good an opportunity to miss as it could mean we sell our NHS services to the US. However, this is only one side of the picture on the other thousands if not millions of jobs will be lost, big public authorities could be nationalised and our constitution faces a future in tatters. There is huge outcry for a referendum on this issue. However, despite the TTIP being a constitutional nightmare it is unlike to result in a referendum come as it seems Mr Cameron has made up his mind.

Tuesday, 23 September 2014

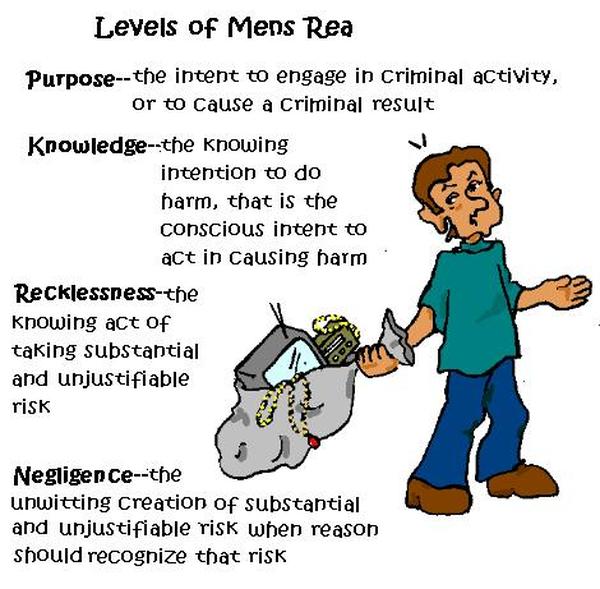

Recklessness and Intention- a criminal law conundrum

The value of intention and recklessness in English Criminal Law

Intention and recklessness are

both vital in English criminal law. It is a defendant’s intention which is

crucial when courts decide if they had a guilty mind and subsequently whether

they should be punished. Recklessness is vital when deciding the facts of a

case and whether the defendant should be punished for not adequately assessing

the risks of the criminal act they are charged with. Intention and recklessness

can both provide the mens rea element of crime which allows a defendant to be

convicted of a crime. In reality, this means that recklessness and intention

carry different punishments but both can be used to ensure that the English criminal

law is effective in punishing people who do not consider risks or intend to commit

a crime. This article is going to examine what is meant by intention and

recklessness, the ways in which they are similar and different and the reasons

why there has been uncertainty surrounding their definitions.

|

| Image source: http://lawatleeds.weebly.com/mens-rea.html |

Intention

Firstly intention, intention is critical when a court decides whether or

not a defendant should be convicted a crime. In order to define intention we

must break it down into two forms: direct and indirect intention. Direct intention is the aim of the defendant. This is essentially,

whether the defendant would consider his action a failure if a desired

consequence did not occur as a result of his action. A case which helps define

direct intention is R v Mohan[1],

in this case Mohan was asked to slow down policeman, he did, but when he got

near the policeman he accelerated towards

the policeman who had to jump out of the way to avoid being knocked over. Mohan

was convicted of dangerous driving after it was judged that by accelerating the

car towards the policeman he had direct intention to kill or seriously harm the

policeman. This is summarised in the appeal judgement of James LJ where he

states that the appeal has failed because:

‘The charge is an attempt to cause bodily harm

by wanton driving. It has to be shown to you that the appellant deliberately,

without justification, irresponsibly, drove his vehicle in such a manner as was

likely to cause some bodily harm.’

Indirect intention is found

when the defendant may intend a consequence

although that consequence is not their objective if it is foreseen. A

case that helps define indirect intention is R v Woollin[2].

In this case Woollin threw his baby across the room in a fit of rage. He argued

that he was aiming for the pram and had no intention of killing or harming his

baby. The baby missed the pram and hit a hard surface which fractured his skull

and later died as a result of his injuries. At first instances and at appeal Woollin

was convicted of murder. His conviction was quashed by the House of Lords where

his murder conviction was substituted for manslaughter on the grounds that he

did not have direct intention to kill his baby and that his intention was

indirect. The House of Lords used Lord Lane LJ’s judgement from R v Nedrick[3] to justify

convicting Woollin of manslaughter. Lord Lane LJ stated that a defendant can

only have direct intention when:

‘The

defendant recognised that death or serious injury would be virtually certain,

barring some unforeseen intervention, to result from his voluntary act’

Wollin realised that there was a risk of serious

injury to his baby but he did not believe this risk to be virtually certain and

so he was not convicted of murder.

Recklessness

There are two forms of recklessness: subjective and

objective. Subjective recklessness is defined in R v Cunningham[4]. In this case Cunningham ripped a gas

meter off of a wall, the gas then leaked out and poisoned the victim. It was

judged that Cunningham had malice because ripping the gas meter off the wall

was reckless. Cunningham was convicted

at first instance but his appeal was accepted because he did not believe that

the victim would be harmed. In this case the defendant is aware of the risk and

acts recklessly and so he is said to be subjectively reckless. Objective

recklessness occurs when it does not need to be proved that the defendant was

aware of the risk, if the risk is was obvious one. A person is objectively

reckless when they create a risk without giving thought to it. Objective recklessness differs from

subjective recklessness because the defendant does not have to be aware of the

risk, they need only take a risk that a reasonable person would have foreseen.

A leading case that helps define objective recklessness is R

V Caldwell[5].

This case creates

the model direction for objective recklessness as

it was judged that a person is reckless for the purpose of criminal damage if

he does an act which creates an obvious risk that property will be destroyed or

damaged and when he does that act he either has not given any thought to the

possibility of there being such risk or has recognised that there was such risk

and has nonetheless gone on to take it. Caldwell has since been overruled by

the judgement in R v Gemmel[6] where the defendants aged

11 and 12, lit some newspapers which set fire to a wheelie-bin which set fire

to a shop, causing £1,000,000 of damage.

On appeal they were found not guilty of arson as the jury believed that

Caldwell was wrongly decided. The Criminal Damage Act 1971 states that a person

is guilty of an offence when they are:

‘(a) intending to destroy or damage

any property or being reckless as to whether any property would be destroyed or

damaged.’[7]

Intention and recklessness are similar

in some respects[8]. Firstly they both form

part of the mens rea of crimes. For

example in a murder trial intention to kill must be proven in order for the

defendant to have had the necessary mens rea to be convicted of homicide[9].

Likewise it must be proven that the defendant was driving recklessly in order

for him to have the necessary mens rea to be convicted of causing death by

careless or inconsiderate driving[10].

Both intention and recklessness are metal states that the defendant might

experience when he is performing the actus reus of a crime. Also they both have

clear links to risk. Intention involves the conscious taking of a risk in order

to achieve an aim and recklessness involves taking an unjustifiable risk either

consciously (subjective recklessness) or unconsciously (objective

recklessness).

Differences between recklessness and intention

There are differences between

intention and recklessness. It could be argued that intention is more thought

out than recklessness[11].

When a defendant has intention to commit a crime they are taking a risk in

order to achieve an aim. They have voluntarily chosen to take this risk and are

taking it as method of achieving their intention. Whereas recklessness is seen

to be more careless, when a defendant is reckless they may be aware of the risk

they are taking but they are not taking the risk in order to achieve anything. Culpability

is also a major difference between intention and recklessness. It is widely

believed that defendants with an intention to commit a crime deserve punishment

because their mental state is guilty. However when it comes to objective

recklessness there appears to no culpability because the defendant was not even

aware of the risk that was being taken.

The final difference between intention and recklessness is the link they

have to a reasonable person. Intention can be considered outside of what is

reasonable. A defendant can intend to commit a crime both rationally (for

example calmly calculating how to kill someone) and irrationally (shooting

someone in a fit of rage but still intending to kill them) either way this

intention is part of a guilty mental state. Unlike intention, recklessness must

be considered in relation to a rational person. Subjective recklessness is still

irrational even though the defendant was aware of the risk, what makes it

reckless is that a reasonable person would not have chosen to do it. Objective

recklessness is always judged in relation to a rational person and cannot exist

if it is not considered in relation to a rational person.

The uncertainty surrounding recklessness and intention

Many uncertainties surround the

definitions of intention and recklessness. This is mainly because three

questions arise: should being reckless be punished? Should it matter if the defendant

considered risk? Should we measure a defendant’s taking of a risk against a

reasonable person? Firstly it is

uncertain whether recklessness should be punished. In order to decide we need

to look at the function of punishment in the criminal law. If punishment is a

means of deterring future offenders,[12]recklessness

should be punished so that in future people take time to consider risks. If

punishment is part of a paternalistic criminal law system,[13]

subjective recklessness should be punished as it could stop citizens taking unjustifiable

risks which could harm themselves and others but objective recklessness should

not be punished because it seems unjust for someone to be punished for taking a

risk they were unaware of. Or perhaps the criminal law is there to protect

society therefore all recklessness should be punished in order to prevent harm

to society. Secondly when deciding whether it should matter if the defendant

considered risk we must consider the effects on society. If it doesn’t matter

society could suffer because people could take risks knowing they cannot be

punished. However if it does matter, there are many implications for

legislation. For example: how do we know what risks should be considered? Are

some risks too unlikely to need consideration? Should defendants consider all

risk no matter how small? Thirdly it can be argued that we should measure a

defendant’s taking of a risk against a reasonable person because this is a good

way of judging what is acceptable and it helps us to predict outcomes based on

what a reasonable person would do. However it could also be argued that

everyone is different and so we should not be compared to a set reasonable

standard as it takes away our individualism and in reality we are not all the

same.

To conclude, intention and recklessness

are both crucial parts of the mens rea of crimes. They are similar because they

are both mental elements in crime and link to risk. They differ because

intention is about the defendant’s aim whereas recklessness is about the

careless taking of risk. There are many uncertainties surrounding the

definitions of intention and recklessness because it is not clear why

recklessness is punished or why it should matter that the defendant considered

risk and there are issues with comparing each defendant to a set ‘reasonable

man’. In order to clarify the definitions of intention and recklessness we need

to look at the function of the criminal law, the effect different definitions

have on society and the way in which the definitions could change how risk taking

is viewed by society.

[1] R

v Mohan [1975] 2 All ER 193, CA

[2] R

v Wollin [1998] 3 WLR 382

[3] R

v Nedrick [1986] 3All ER 1

[4] R

v Cunningham [1957] 2 QB 396

[5] R

V Caldwell [1982] AC 341

[6] R

v Gemmel [2003] UKHL 50

[7] Criminal

Damages Act 1971 s1

[8]

Lucy William, ‘controversy in the criminal

law’ (2006) http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1748-121X.1988.tb00646.x/full

accessed 15/11/12 02:35

[9]

Homicide Act 1957

[10]

Road Traffic Act 1988 s2B

[11] Andrew Halpin

‘Definitions and

directions: recklessness unheeded’ (2006)

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1748-121X.1998.tb00019.x/abstract

accessed 15/11/12 23:30

[12] Paul H Robson and John M Darley ‘Does Criminal

law deter? A behavioural science investigation’ (Oxford journal of legal studies volume 24 no 2, 2004, p 173-205)

http://webscript.princeton.edu/~psych/psychology/research/darley/pdfs/Does%20Criminal%20Law%20Deter.pdf accessed 10/11/12 15:00

[13] Richard

Tur ‘ Paternalism and the criminal law’ (2008) http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1468-5930.1985.tb00031.x/abstract

accessed 12/11/12 at 12:05

Saturday, 6 September 2014

Contract Formation: more than just consensus between parties?

Contracts and consensus

Every day

we form contracts, sometimes these are obvious such buying a property but

sometimes the contracts we enter into are barely noticeable for example buying

a newspaper. Establishing consensus between the parties is a major part of

contract formation however this article is going to examine how contract

formation is more than just mere consensus between parties. Consideration,

intention to create legal relations, communication of the offer and certainty

of terms are all key factors in contract formation. Contracts are not just

about establishing consensus between parties they also establish legal

relations and dependence between the parties.

It is

important to note exactly what is meant by ‘consensus between the parties’. A

consensus between parties is made up of an offer and an acceptance. These are

essential when creating a legally binding contract and help courts to identify

exactly when a contract was formed and consensus was reached between the

contracting parties. An offer is ‘a statement by one party to enter into a

contract on certain terms which he has put forward’[1]

It must be knowingly and unconditionally accepted in order for a contract to be

formed. A key case on this point is Gibson

V Manchester City council.[2]

In this case it was judged that a contract was not actually formed because an

offer was never made. Gibson received a letter from the council saying that

they ‘may be willing’ to let him buy his council house. The court judged that

this was not an offer but actually a supply of information and so Gibson could

not buy his council house because consensus between the parties in the form of

an offer and acceptance had never actually occurred. In order for an offer and

an acceptance to establish consensus between the parties the acceptance must

show that the offeree agrees to all of the important terms of the offer. When

consensus between the parties is reached the ‘two minds must have come together’[3]

meaning that the promisor and the promisee must agree on all of the important

terms of the contract.

Contract Formation- Consideration

Next we shall consider other factors which

play an important role in contract formation. The first of which is

consideration. Consideration was defined by Justice Lush as: ‘ some right,

interest profit or benefit accruing to the one party, or some forbearance,

detriment, loss or responsibility given, suffered or undertaken by the other.’[4]

In reality this means that the parties become

reliant upon each other because they act to their detriment and the other

party’s benefit on the reliance of the promise. Consideration does help to

establish consensus between the parties but it also establishes dependence

between the parties, another key piece of evidence to suggest a contract has

been formed. Consideration is deemed good so long as it is not an obligation

which arises under law independent of the contract[5],

an obligation which arises under a contract with a third party[6],

past consideration[7] or

an obligation which exists under a contract with a person who has made a new

promise for which the existing obligation is alleged to provide good

consideration.[8]

In the case of Chappel & Co v Nestle,[9] Nestle offered customers a record if they sent in

money and three Nestle wrappers. The question raised was: are used Nestle wrappers

good consideration? The Court found that

they were good consideration because even trivial things of very little

economic value are adequate consideration. This case demonstrates how

consideration ‘must be sufficient but need not be adequate’[10] and

really shows how the courts can use consideration to establish consensus

between the parties but also the reliance of the parties upon one another.

These are the court’s concerns not whether the contract was valuable.

Intention to create legal relations

Next we shall consider intention to create legal relations. Whilst

intention to create legal relations does help to establish consensus between

the parties, it also allows the contract to become legally binding. Intention

to create legal relations shows that the parties were aware that court action

could arise out of their consensus. Therefore they are not just agreeing

between themselves but also preparing for the future consequences of their

contract. This means that the parties can go to court in order to enforce

legally binding contracts and that the courts can ensure that parties who

breach contracts have to fulfil their contractual duties or pay compensation to

the other party. If all agreements could be enforced by courts they would be

inundated with cases and this is not practical. Subsequently, intention to

create legal relations is only usually recognised in commercial agreements and

not domestic agreements. An example to explain this rule is Jones v Paddavatton[11].

At first instances the court ruled that the

contract is not legally enforceable because there is no intention to create

legal relations as it is a domestic agreement. On appeal Fenton Atkinson LJ

explained that the appeal had failed because the contract was not legally

binding as the conduct of the parties indicated lack of intention to create

legal relations. Also the arrangement is too vague and the daughter's statement

included: 'what kind of mother sues her daughter?’[12]

Overall this shows how the intention to create legal relations establishes more

than just consensus between the parties but also an awareness that legal

consequences can arise from their agreement. This means that the rules of

contract formation not only elaborate on the requirement of establishing

consensus between the parties but also to establish that the parties are aware

of the consequences of their agreement.

Communication

Communication

of the offer is another important rule of contract formation. How the offer is

communicated is important in establishing consensus between the parties as it

is the way that the offeree finds out about the offer. It also helps to put a

time limit on the consensus so that the parties are not bound forever. In the

case of Payne v Cave[13]

it was judged that an offer expires after a ‘reasonable’ amount of time. This

is to ensure that the offeror does not get bound to receive and act on

acceptances forever. Much like intention to create legal relations this ensures

that the law on contract formation is practical and that all parties to the

contract know when acceptances have to be made. Communication of the offer is

also crucial in ensuring that all parties know that a contract has been formed

and ensures that the law only enables contracts to be formed when all parties

are aware that the offer and acceptance exist. A leading case on this point is Dickinson v Dodds[14]where

it was judged that the offeree

can be told by anyone that the offer no longer stands, it does not have to be

the offeror who tells the offeree that the offer has been revoked. Essentially

showing that it does not matter who tells the offeree about the offer as long

as they are trustworthy so that it can be ensured that both parties have

knowledge of the progress of the contract formation or offer revocation.

Certainty of terms

A final point to examine is the certainty of terms. Terms of a

contract must be understood between both parties to mean the same things so

that a contract can be executed. The court’s role is to enforce

and interpret what is agreed not create contracts.

Therefore if the parties agreement is incomplete or uncertain it is not

enforceable as a contract because uncertainty of terms means there is no

consensus between the parties (ad idem). There are two leading cases on this matter

May and Butcher ltd v The King[15]and Hillas and Co v Arcos.[16] In May and Butcher Ltd V the King,

the court held that there is no agreement on prices or dates and so no

concluded contract because there is no certainty of terms. Viscount Dunedin

stated that a concluded contract is 'one that settles everything that needed to

be settled.' [17] In this case there was an

arbitration clause containing a mechanism to work out a price but the court

said that the arbitration clause is not a price calculation mechanism. In the

other leading case Hillas and Co v Arcos,

the court said there was a contract for 1931 because it was implied in the

first contract and the conduct of the parties proved that the parties had an intention

to create legal relations. The cases of Hillas

and Co v Arcos and May Butcher ltd v

the King can be reconciled because in Hillas

and Co v Arcos the contract was almost complete and the parties’ conduct

gave the court away to determine what they intended and in May Butcher ltd v the King the greatest extent of required

certainty is displayed as since the required certainty has become more

flexible. Essentially, this shows how certainty of terms is key when

establishing whether the parties have reached consensus but also helps courts

to settle the cases brought to them as they can identify the intentions of each

of the party’s and remedy the situation accordingly.

Conclusion

After

examining a few of the main rules of contract formation this article concludes that

the rules of contract formation are primarily concerned with establishing

consensus between the parties but they can also be used to establish other key

facts such as reliance between the parties, the knowledge of the parties that

they have entered into a contract, that the parties know that there could be

legal consequences to their consensus and to ensure that the law on contract

formation is practical. All of the rules of contract formation that have been

examined help to establish consensus between the parties. Consideration also

helps to establish reliance between the parties. Intention to create legal

relations helps to establish that the parties know there could be legal

consequences to their consensus and makes the laws on contract formation

practical. Communication of the offer establishes the knowledge of the parties

and their understanding of the agreement. The need for certainty of terms helps to

establish that all parties had knowledge of the offer and acceptance. As a

result it is reasonable to say that the rules on contract formation are an

elaboration of the requirements of establishing consensus between the parties

but this is not their only function other facts also play a role.

[1] Ewan Mckendrick, Contract law text cases and materials (Fifth edition published

2012) p 44

[2] Gibson v Manchester City Council [1974] All E.R 842

[3] Carlill v

Carbolic Smokeball co [1893] 1 QB 256

[4] Lush

LJ in Currie v Misa [1875] LR 10 Ex 153, 162

[5]

Collins v Godefroy [1831] 1 B&Ad 950

[6]

Pao On v Lau Yiu Long [1980] A.C 614

[7]

Roscorla v Thomas [1842] 3 QB 234

[8]

Stilk v Myrick [1809] 2 Camp 317

[9] Chappel

and co v Nestle [1961] AC 87

[10] Ibid

[11]

Jones v Padavatton [1969] 1 WLR 328

[12] Ibid

[13] Payne

v Cave [ 1789] 3 T.R 148

[14] Dickinson

v Dodds [1876] 2 ch.D 463

[15]

May and Butcher ltd v the King [1934] 2 KB 17n

[16]

Hillas & Co v Arcos ltd [1932] 147 LT 503

[17]

Viscount Dunedin in May and Butcher ltd v the King [1934] 2 KB 17n

Wednesday, 27 August 2014

Constitutional Crises- Dicey's concept of parliamentary sovereignty is still relevant

Dicey and Parliamentary Sovereignty

Dicey's argument that parliamentary sovereignty in the UK constitution means that parliament has:

Dicey's argument that parliamentary sovereignty in the UK constitution means that parliament has:

' the right to make or unmake any law whatever; and

further that no person or body is recognised by the law of England as having

the right to override or set aside the legislation of parliament.' [1]

|

| Image Source: http://thoughcowardsflinch.com/2010/03/23/the-tories%E2%80%99-secret-plans-for-the-end-of-parliamentary-sovereignty/ |

First to be

considered is the reason Dicey believed parliamentary sovereignty to be this

way. For the sake of this article it will be assumed that Dicey intended his

definition to be normative in that he was describing how parliamentary

sovereignty should be ideally. This article will argue that Dicey's view of

parliamentary sovereignty can still be reconciled with constitutional reality.

Since Dicey was writing, the European Communities

Act[2],

judicial review and the Human Rights Act[3] have

been used to argue that his view of parliamentary sovereignty cannot be

reconciled with constitutional reality. This article will argue that Dicey's view

of parliamentary sovereignty is still accurate in constitutional reality on the

grounds that the UK parliament signed the European Communities Act, judicial

review reinforces parliamentary sovereignty and the Human Rights Act does not

actually make contradictory acts of UK parliament invalid.

The relevance of the European Communities Act

Many would argue that t the

European Communities Act could be seen as evidence that suggests that parliament no

longer has ‘the right to make or unmake any law whatever’[4] as Dicey

proposes but instead proves that parliament can in fact be overruled by EU law.

In response to this it can be argued that Dicey is

in fact right in saying that ‘parliament can make and unmake’[5] any laws

because it was parliament who signed the European Communities Act voluntarily

and so the sovereignty they gave to the EU can be retained at parliament’s will

therefore they can regain absolute sovereignty. The case of Thoburn[6] even goes do far as to

suggest that the European Communities Act

1970 was created by Parliament. So adherence to EU law is merely courts

following the will of Parliament. Also Dicey suggests that nobody has the right to override the rules of

parliament which again, despite the European Communities Act, is true in

constitutional reality. Although the EU can say that UK acts of parliament do

not conform to EU legislation it is the parliament themselves who choose to

change acts of Parliament in order to make them comply with EU law. If they did

not do this then they would be in breach of the European Communities Act but

whilst this is not a favourable outcome it is possible.

The point to be noted is that all of the choices related

to the transfers of sovereignty due to the European Communities Act were made

voluntarily by parliament and can be unmade if parliament wishes. This is

explained in the case of Factortame [7] which exemplifies, through the courts suspending the

Merchant Shipping Act 1998, how national courts can strike down Act of

Parliament's that contravene EU law. In his judgement Lord Bridge explained how

EU law should override acts of parliament because it was parliament’s decision

to join the European Community and parliament’s decisions must be respected. Therefore Dicey was completely right in saying that

parliament has: ‘the right to make or unmake any law’[8]

Judicial Review and judge's creativity

Judicial Review and judge's creativity

Another counterpoint to the argument that Dicey’s

account of parliamentary sovereignty can be reconciled with constitutional

reality is one which occurs as a result of judicial review. This counterpoint

is based on the views of Paul Craig[9] who argues

that judicial review is about judge’s creativity and not parliamentary

sovereignty. Craig’s argument counters the argument in this essay by claiming

that the content of judicial review is about judges using their creativity to

make laws to govern public bodies and stop them acting unfairly. If this is

true then Dicey’s account of parliamentary sovereignty becomes very difficult

to reconcile with constitutional reality.

Fortunately it can easily be argued that judicial

review does in fact reinforce Dicey’s view that parliament does have complete

sovereignty in the UK. The strongest argument is based on the ideas of Professor

Christopher Forsyth who argued that:

‘The

judicial achievement in creating modern law did not take place in a

constitutional vacuum. It took place against the background of sovereign

legislature that could have intervened at any moment,’[10]

This demonstrates how parliamentary sovereignty

is the basis of judicial review. It is a strong point that judicial review

cannot be used to question acts of parliament and if courts question Acts of

Parliament, in judicial review cases, all they can do is request that

parliament re-think the act. Courts can in no way force parliament to change an

act. Judge’s creativity in judicial review cases is not about overriding

parliamentary sovereignty but is actually about the judges extending the law to

cover situations that parliamentary sovereignty does not cover. In this sense,

judicial review is actually supporting Dicey’s view that parliament have

ultimate power within the constitution. By

having this system whereby the courts cannot question parliament’s act and

decisions constitutional reality is actually very compatible with Dicey’s view

that no one can override parliamentary laws.

The Human Rights Act 1998

The final counterpoint to the argument that

Dicey’s account of parliamentary sovereignty can be reconciled with

constitutional reality is a point put forward after examining the Human Rights

Act. It can be argued that the Human Rights Act 1998 overrides parliamentary

sovereignty is the UK in a way that Dicey deems impossible. Article 6, section

2 of the TEU) [11] imposes an obligation on Member States to respect

the rights arising from the European Convention of Human Rights.

One could interpret this to mean that the Human

Rights Act is part of law in member states of the EU because EU law has

supremacy over national law and so on these grounds Dicey would be inaccurate

in saying: ‘no person or body is recognised by the law of England as having the

right to override or set aside the legislation of parliament.’ [12] However

it could be argued that the Human Rights Act supports the acts which the

supreme UK parliament has already created. If this is the case then EU law is

merely a supporting extension of the UK law which was created by the sovereign

UK parliament. This is the view taken by

Lord Millet in Ghaidan v Godin-Mendoza where he judges: ‘Sections 3 and 4 of

the human rights act were carefully crafted to preserve the existing

constitutional doctrine.’[13] This

appears to mean that the Human Rights Act was created as a result of

parliamentary sovereignty to conform and not override rights that already

existed as a result of acts passed by parliament. If this is the case then

Dicey was right. Subsequently this means that every counterpoint mentioned in

this essay can be overcome and that the argument that Dicey’s account of

parliamentary sovereignty can still be reconciled with constitutional reality

is a very strong.

Conclusion

To conclude, after a concise examination of the possible flaws with the argument, it can be reasonably concluded that Dicey’s account of parliamentary sovereignty can still be reconciled with constitutional reality. The counterpoints that the European Communities Act, judicial review and the Human Rights Act undermine Dicey’s account of parliamentary sovereignty are all very clever arguments, however they can be overcome by looking more closely at the fundamental choices that parliament has made (for example voluntarily signing the European Communities Act). It is when we look closer at the intricacies of the European Communities Act, judicial review and the Human Rights Act that we can see that parliamentary sovereignty was not actually a victim of these concepts but something that they all support and conform to.

[1] AV

Dicey ,Introduction to the study of the law of the constitution (first published 1885, London: Macmillan

& Co 1959) p 39

[2] European

Communities Act 1972

[3] Human

Rights Act 1998

[4] Dicey, cited above at n1 at p39

[5] Dicey, cited above at n1

[6] Thoburn v Sunderland City Council [2002] All ER (D) 223

[7] R v

Secretary of State for Transport, ex parte Factortame Ltd and others [1999] All ER (D) 1173

[8] Dicey, cited above at n1

[9]

P.Craig, Britain in the European Union’ in J .Jowell and D.Oliver The changing

constitution p 91-99

[10] Christopher Forsyth, Of

Fig leaves and fairy tales: The Ultra Vires doctrine, the sovereignty of

parliament and judicial review (first published 1996) p 122

[11] TEU

(treaty of Maastrict 1992) s2

[12]Dicey,

cited above at n1

[13] Ghaidan v Godin-Mendoza [2004] UKHL 30 [57]

Wednesday, 13 August 2014

Human Rights Act- the perfect combination of rights protection and judge power

What is the Human Rights Act?

The Human Rights Act 1998 (HRA)[1]

was created using some of the rights set out in the European Convention on

Human Rights (ECHR) and seeks to preserve the fundamental human rights of

British citizens. This popular argument that the HRA excessively empowers judges in order to protect fundamental rights demands an examination of two opposing positions. First in order for the HRA to effectively protect human rights judges must be

excessively empowered and second the excessive empowerment of judges is not

necessary for the HRA to achieve the protection of human rights. This article argues the latter.

|

| Image source: UK Human Rights Blog |

Le Sueur describes human rights in their most basic

form as ‘basic, inviolable, fundamental and constitutional.’[2]

The HRA was formed from this basis in order to protect British citizen’s human

rights and ‘bring rights home’[3].”

Gardbaum explains how the HRA balances: ‘Recognition

and effective protection of certain fundamental rights or civil liberties’ and ‘a proper distribution of functions and

decision making power between courts and the elected branches of government.’[4]

Excessive power to judges?

From a Diceyan viewpoint ‘excessive power’ would suggest

that judges no longer just fulfil their function as interpreters of statute and

implementers of the law but go on to infringe on the powers of the executive or

the judiciary. Assuming this is what is meant by ‘excessive power’ then section

3 of the HRA could be interpreted to be a grant of excessive power to judges.

In Re S[5]

Lord Nicholls famously said that judges had ‘crossed the boundary between

interpretation and amendment’ if this is true then this is a good example of

judges being given excessive power. However there has been much criticism of this

view, section 3 of the HRA clearly states judges should ‘interpret’ and not

amend statute ‘so far as is possible’. The wording of the statute clearly

states that the judges cannot change statute to the extent that parliament’s

intention is no longer evident.

This article advocates the argument that the HRA

effectively protects human rights without giving the judges excessive power. The role of the judges in the implementation

of the HRA section 3 is to interpret legislation ‘so far as is possible’[6]

to make it compatible with the ECH. Many believe that this crosses the boundary

between interpretation and amendment. Ewing, Gearty[7]

and Klug all argue that section 3 damages parliamentary sovereignty. Klug said R v A[8]:

‘turned parliamentary intention on its head.’[9]

If so, there are implications for parliamentary sovereignty because judges

would effectively be legislating. A strong counter point to this would be Lord

Slynn’s point in R v A[10]

‘The Human Rights Act reserves the amendment of primary legislation to

Parliament. By this means the Act seeks to preserve parliamentary sovereignty.’

Kavanagh proposes that when using section 3 judges should consider social

policy, parliament’s response to the decision, justice for the individual in

the case remedy and the jurisprudence of the ECHR[11].

This provides factors for judges to think about which prevents them having

‘excessive power’ under the HRA and means that the HRA is a good illustration

of how human rights can be protected without giving judges excessive power. Gardbaum

counters by explaining that section 3 is excessive power for judges and that

section 4 should be used instead as it allows parliament to ultimately change

the law to be convention compatible. To overcome this criticism it must be

remembered the HRA itself is an act of parliament and so by giving judges any

power it can be assumed that it is acceptable to parliament to allow them to

interpret statutes in order to make them convention compatible. Also statutes

cannot be interpreted in a way that does not go ‘with the grain’[12]

of the statute and so parliamentary sovereignty is preserved.

Section 4 of the Human Rights Act 1998

Many academics believe section 4 of the HRA reduces the

separation of powers by allowing judges to declare statute incompatible with

the convention rights because in response to a section 4 declaration, section

10 allows a fast track remedial procedure to take place. Many believe that this

is a Henry VIII clause that contradicts parliamentary sovereignty as it allows

government ministers to amend statute by using a declaration of incompatibility[13].

Young counters this point by explaining

that section 10 only contradicts parliamentary sovereignty when one interprets

the Diceyan concept of implied repeal to mean that future legislation partially

impliedly repeals the prospective Henry

VIII clauses and that section 10 can overturn legislation enacted post

HRA. The decision in Thoburn[14]

(future legislation does not implied repeal prospective Henry VIII clauses)

should be used in all section 10 cases in order to ensure that section 10 does

not override parliamentary sovereignty[15]. Section 4 affirms the separation of powers by

allowing parliament to respond to the judge’s decision. A premise that is

supported by legislative evidence as parliament has amended statute in 11 out

of the 19 declarations of incompatibility cases so far.[16]

This has increased dialogue between the judiciary and parliament because both

are more aware of what their counterparts are doing, therefore the powers remain

distinct and the transparency of the different branches of the legal system is maintained

which ultimately leads to the rule of law being upheld. Therefore judges have

not been excessively empowered and section 4 is what restricts judges having

excessive power because it affirms the separation of powers, helps to uphold

the rule of law and supports dialogue between the judiciary and parliament. Jack

Straw commented through that HRA section 4 ‘the government thought it was

important to enshrine parliament’s sovereignty of the bill’[17]

Parliament effectively used its sovereignty

to allow judges to bring incompatible statutes to parliament’s attention because they deemed this to be the best way to

protect rights. It was parliament’s intention and so the judges cannot be said

to be excessively empowered.

Conclusion

To conclude, the HRA is an illustration of how to

effectively protect rights without ‘excessively empowering’ judges. This view

is opposed because the popular tabloids’ report negatively on the HRA[18]this

puts pressure on politicians to change the HRA and perhaps repeal it and

introduce a bill of rights[19]. Overall this has led to academic response[20]

that is a powerful influence on the public opinion about the power of judges

under the HRA and rights protection in general. By removing the bias caused by

the media we can see the HRA is an ingenious act of parliament which allows the

British constitution’s protection of rights to evolve in a way that is

controlled by parliament’s intentions. Section 3 maintains parliamentary

sovereignty but still allows statutes to be made convention compatible without

parliament having to spend time and money repealing and amending all

questionable statutes. Section 4 supports section 3 by allowing incompatible

statutes to be bought to parliament’s attention but still preserve the

separation of powers, parliamentary sovereignty and the rule of law by only

allowing parliament to decide whether or not statute is amended and allowing a

declaration of incompatibility to be made without statute being deemed invalid.

[1]

Human Rights Act 1998

[2] Le

Sueur, Sunkin , Murkens, Public Law text

cases and materials (First published 2010, Oxford University Press)175

[3]

Secretary of State for the Home Department, Rights Bought Home: The Human

Rights Bill (CM 3782 Oct 1997)

[4] S.

Gardbaum “How Successful and Distinctive is the Human Rights Act? An Expatriate

Comparatist's Assessment” (2011) 74 Modern Law Review 195

[5] Re

S [2002] UKHL 10 (40)

[6]

Human Rights Act 1998 3 (1)

[7] K.

Ewing, ‘The Human Rights Act and Parliamentary Democracy’ (1999) 62 Modern Law

Review 79

[8] R

v A [2005] UKHL 25

[9]

Klug, Judicial deference under the Human Rights Act 1998 EHRLR 125,128

[10] R

v A [2001] UKHL 25

[11] A.

Kavanagh, ‘Unlocking the Human Rights Act: The "Radical" Approach to

Section3(1) Revisited’ (2005) European Human Rights Law Review 259

[12] Ghaidan

v Mendoza [2004] UKHL 30 (33)

[13]

Parte H [2001] EWCA Civ 415, Baiai [2008] UKHL 53 and Thompson [2010] UKSC 17

[14]

Thoburn v Sunderland City COUNCIL [2003] QB 51

[15]

Young, Parliamentary Sovereignty and the human rights act (First published

2008, Hart Publishing) 6-8

[16] Ministry

of Justice, Responding to human rights judgments, Annex A: Declarations of

Incompatibility

[17]

Jack Straw Hansard HC 21/10/98 Col 1300

[18]

The Sun 09/02/11

[19] D.Cameron

Speech (26/06/06)

[20]

Hiebert, Parliament and the Human Rights Act: Can the JCHR help facilitate a

culture of rights?, Oxford Law Journals, vol 4 issue 1

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)